This week sees the 50th anniversary of Bloody Friday. The most violent day of the most violent month of the most violent year of the Troubles.

On Friday 21st July 1972, the IRA planted 23 bombs across Belfast. It was a warm summer’s day. The bombs started to explode early in the afternoon. In total, 19 would detonate in less than 80 minutes. At one point, 6 bombs went off within 3 minutes, 9 within 18 minutes. 9 people were killed, hundreds were injured and thousands were terrorised.

People watching the explosions from higher ground around Belfast said the city looked like it was under aerial bombardment as the bombs set off huge plumes of smoke and debris again and again.

Kevin Myers, an Irish journalist who watched the afternoon unfold from the top of a building on the southern edge of the city centre wrote;

“As the bombings started, thousands of panic-stricken shoppers began to stumble backwards and forwards, seeking safety. The endless explosions, the columns of smoke rising everywhere, the crowds stampeding into one other, declared this simple, inescapable truth: there was no such thing as safety. Long after the last bomb had exploded, terrified people skulked in clusters, paralysed, not knowing where to go, with hundreds of children screaming amid the acres of broken glass.”

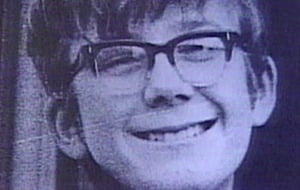

One of the two bombs to kill was a no-warning car bomb left outside a row of shops on the Cavehill Road in north Belfast, well outside the city centre where the majority of the bombs had been located. It was the eighteenth bomb to explode, detonating at 3.15pm. The bomb killed 67 year old Brigid Murray, 14 year old Stephen Parker and Margaret O’Hare, a 37 year old mother of seven. Many more suffered life changing injuries.

Stephen had been helping out in a shop in the row when he noticed a car parked oddly, he looked into it and saw a bomb sitting on the back

Stephen was posthumously awarded the Queen’s Commendation for Bravery medal for his actions that day. His father was Rev. Joseph D. Parker, an Anglican minister and chaplain at the Mission to Seamen. He remembered one of the last conversations he had with Stephen when he asked ‘Dad, what’s this place going to be like when I’ve grown up?’. In the morgue he could only identify his son by his hands, the contents of his pockets and his scouts belt buckle.

Rev. Parker started a peace group following the death of his son called ‘Witness for Peace’. Vigils, services and rallies were held. In November 1972 they placed 436 white crosses on the lawns of city hall for everyone who had lost their life so far that year.

A scoreboard was also set up outside a church in the city centre, updated weekly by Rev. Parker and listing the running total of dead. Maybe it pricked the consciences of those who saw it, but it didn’t deter the perpetrators and it even upset some members of the clergy. “We held services for everybody: soldiers, IRA, all the dead. Unfortunately I was a little bit ahead of my time. A lot of people in my own church didn’t

For the next two years Rev. Parker campaigned relentlessly for peace and reconciliation, but was frustrated by the response from his Church and politicians. Following the collapse of the Sunningdale power-sharing executive in 1974, Rev. Parker announced that he and his family were emigrating, leaving for Canada in 1975. Some said that “he could no longer live with the hatred of those who cannot forgive.” Reverend Parker died in 2018 and his ashes were brought back to Belfast from Canada to be interred alongside Stephen in Roselawn Cemetery.

Another founder member of Witness for Peace was Stephen McCann, a 21 year old Catholic student from the next street to the Parker’s home in north Belfast. Stephen was a committed member of the peace group and had also written ‘What Price Peace’, a song which was sung regularly at many of the vigils and events.

On the evening of 30th October 1976 Stephen McCann was walking his girlfriend home from a disco in Queens University when he was spotted and abducted at Brown Street in Millfield on the edge of the city centre by the Shankill Butchers. That night the Butchers had got drunk and then simply decided ‘to go out and get a taig’ according to the resulting trial. As they drove around the city in a yellow Ford Cortina they chanced upon Stephen and his girlfriend. They pushed her to the ground and bundled him into the car, then drove to a house to pick up a gun and a butcher’s knife before taking him to a loyalist club in Glencairn where his throat was cut and he was shot in the head.

One week after his death his sisters sang his song at a peace rally at Belfast City Hall while 1,662 white crosses were planted on the lawn to remember all the victims of the Troubles to that point.

“What price peace, will it cost us all our lives?

And when there’s no-one left to die,

Will peace come then?

What price peace, is it coming, is it gone?

Have we had our share or is it still to come?”

How we commemorate or memorialise the victims of our troubled past continues to prove challenging for many. It’s exactly 50 years since Bloody Friday and yet, while we have had nearly 25 years of (relative) peace, many of our political leaders still can’t agree on how to commemorate these events. Which is as depressing as it is predictable.

In the words of Eric Lomax, the author of ‘The Railway Man’ who was a British POW forced to work on the Death Railway in Thailand by the Japanese during World War 2, and who later reconciled with his captors –

“Remembering is not enough, if it simply hardens hate. Some time the hating has to stop.”