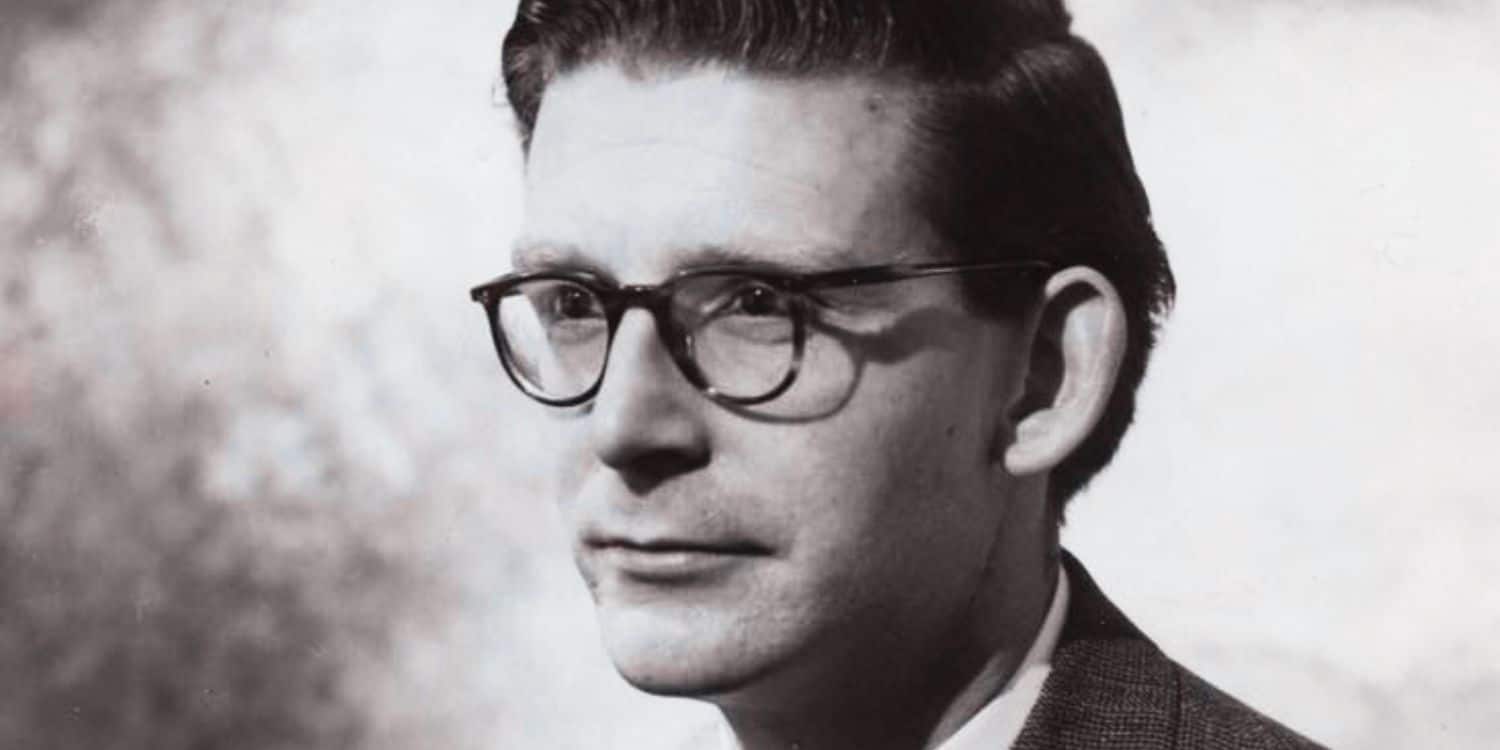

If you have any interest in Belfast architecture you will have heard of Sir Charles Brett (1928-2005), whether as the author C.E.B. Brett, or Charlie Brett as he was generally known.

His best known book, ‘Buildings of Belfast 1700-1914’ will be familiar to anyone who has an interest in local history. Brett was a fascinating figure; a solicitor who was variously a politician, historian, artist, journalist, writer and conservationist.

Charles Brett’s early life

Charles Edward Bainbridge Brett came from an Anglo-Irish family which could trace itself back nine generations in Ireland. For more than 200 years the Bretts ran businesses in Belfast, first as merchants, then later as solicitors and barristers.

Brett was born in Holywood, just outside Belfast, and at the age of nine he was sent to boarding school in Yorkshire (which he liked) and then on to Rugby (which he did not).

Narrowly missing conscription, he read history at New College, Oxford where he enjoyed himself enormously, chairing the Poetry Society, going on pub crawls with Dylan Thomas and spending the summers traipsing round Italy and France.

Life in Paris

When he graduated, he took off to Paris, where he found a part time job in the English service of the French radio station La Radiodiffusion Francais.

He was surprised to be greeted by his new boss with the words “Ah, vous venez de Belfast. Vous etes, sans doubte, comme moi membre du Tramways Club de Belfast?” (the Tramwaymen’s Club was a drinking den near the docks, familiar to anyone who had served in a Navy).

The tiny team was expected to produce three hours of programmes each night, so Brett had to turn his hand to everything, including broadcasts. He once had to announce that ‘Jean Cocteau’s cat has won a prize in a cat show’ but instead blurted that ‘Jean Cateau’s cock has won a prize in a cock show.’

He stayed in Paris for a year, working his way up to writing a gossip column for the Continental Daily Mail, but then returned to Belfast to join the family law practice, L’Estrange & Brett.

“A black, boring provincial city”

He feared that Belfast would be a “black, boring provincial city”, but instead found that “in the 50s and 60s, life in Belfast was probably more invigorating and rewarding than in Dublin, Glasgow or any other provincial city of the British Isles.” He soon counted among his friends the broadcaster James Boyce, the artist Markey Robinson, the playwright Sam Thompson and the columnist Ralph Bossence.

In the 1950s he appeared in series of local radio programmes that ended up running for over a decade, based on the national ‘Any Questions’ format – a panel answering topical question from members of the public.

Local politicians and distinguished guests (including Professor Jacob Bronowski, author of The Ascent of Man) also took part and in Brett’s words it had “a considerable effect in relaxing the old sectarian tensions and subjecting to reasoned (and good-mannered) argument the attitudes and activities of nationalists and unionists alike.”

The Sunday Swings affair

He also became interested in local politics. He identified as a European, with little interest in nationalist or unionist arguments, so in 1950 he joined “the tiny and feeble Northern Ireland Labour Party”, where his journalistic experience led to work drafting press statements and election leaflets.

He eventually became the party leader, but the ‘Sunday Swings’ affair (the party’s policy was that playground swings should not be chained up on Sundays, as Unionist councils did in those days – but when the issue was voted on in Belfast City Hall, Protestant NILP members broke rank and voted to keep the parks closed) meant the party lost its credibility as a non-sectarian alternative.

Their failure to successfully communicate to the British Labour Party the impending risks in the late 1960s was also a huge frustration to Brett. One Labour minister told him, “This is the twentieth century, not the seventeenth century, and it is just not possible to believe that the religious divisions in Ireland could lead to violence ever again.”

In 1969 he effectively retired from politics, writing in his memoir, “A dozen times since then I have been reproached by friends in the British Labour Party, one at least today a cabinet minister, with the words: ‘Why ever did you not warn us of what was coming?’ I have never yet succeeded in finding words adequate to reply to that question.”

Buildings of Belfast

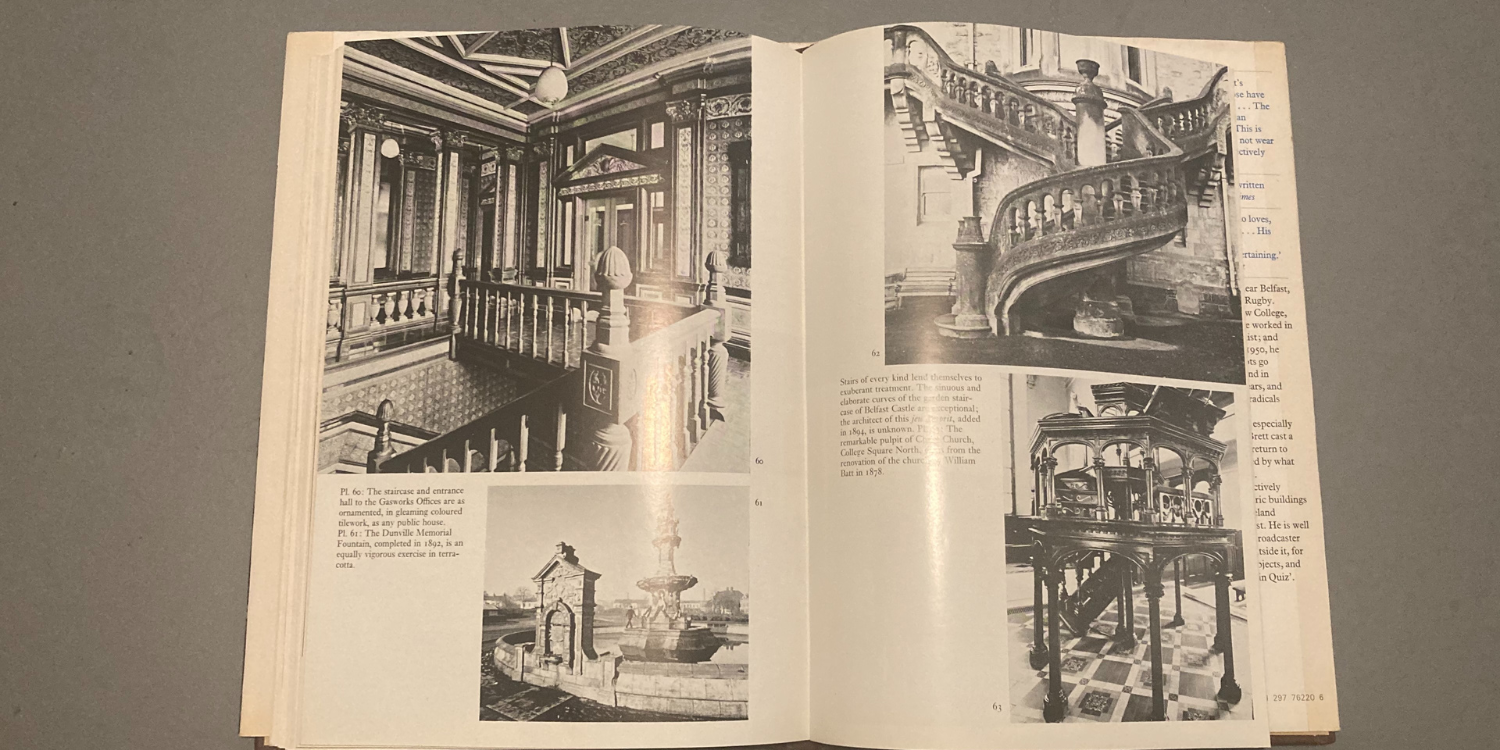

In 1956, he had been invited to join the regional committee of the National Trust. When he asked what books on Northern Irish architecture he should read to equip himself for the role, he was told that there were virtually none.

So in 1957 he started researching his first book, ‘Buildings of Belfast 1700-1914’, a labour of love which was published in 1967 (“…in the nick of time. A year after it appeared, the Troubles began; and soon after, the bombing campaign.”). The revised edition, published in 1986, has footnotes cataloguing the fate of many of the buildings – many were by then marked “bombed” or “demolished”.

Brett’s Buildings of Belfast 1700-1914 recorded many lost Belfast buildings

Brett during the Troubles

His account of life in Belfast in the Seventies in his memoir/family history ‘Long Shadows Cast Before’ is a fascinating glimpse into a very different experience of the Troubles – that of a slightly eccentric professional trying to run the family law firm in the midst of the conflict.

He describes the first time his city centre offices were bombed, in 1972, as he was out for dinner with friends; hearing a series of heavy explosions he remarked that someone was getting a battering that night.

He got home at midnight to discover that it was his own offices which had been badly damaged in a large car bomb; it took five years to complete the rebuilding. By the late 1970s he was so used to bomb warnings and evacuations that he was often seen using a traffic bollard near the City Hall as an open-air desk until the all-clear was given.

He grumbles about the effects of the 1974 Workers Strike, which led to the sewage stations shutting down and the subsequent risk of raw sewage flooding of his basement offices.

He decided that the best precaution was to cycle round his friends’ houses, collecting all their children’s plasticine to seal the safes and filing cabinets. “In the event, the pumping stations did not stop, and the hardest part of the return to normal after the strike had ended proved to be the removal of the plasticine caulking.”

However, he managed better at home – after initially feeling helpless in the face of the power cuts, each night he lit a fire and some candles, opened a bottle of claret and imagined himself returning to the simpler life of his eighteenth-century ancestors. It probably helped that his wife and family were in England at the time.

He also gives us perhaps the most middle-class account of a Belfast bombing that I’ve ever come across:

“On the evening of 13 June 1974, I arrived home from work as usual around six o’clock. ‘Home’ was a comfortable four-square manse in the Malone Road area of Belfast. It was a very pleasant summer evening; the long avenue of lime trees was in full leaf. The children were away. My wife was waiting for me with the news: ‘They say there’s a car-bomb in the park behind us’…There had recently been a good many bombs in the city, but there had also been a vast number of hoaxes and scares. ‘I don’t believe it’ I said; ‘let’s sit down and have a glass of sherry. But we had better keep away from the windows.’ (There is always a quandary in a bomb-scare: if windows and doors are opened, the damage is minimised, for the blast wave can travel freely till it spends itself: but anyone in the process of opening windows when the explosion comes may be dreadfully mutilated by flying glass) We decided to leave the windows alone, poured ourselves sherry, and sat down in our usual chairs on either side of the fireplace in the sunny drawing-room.

“Five minutes later, as we were sitting peaceably chatting and sipping, there was the loudest explosion I have (yet) heard; a sucking wave of blast; and all the glass in every window in the room fell shimmering and tinkling to the ground. By good fortune, it was the secondary inward wave, not the initial outward blast, that broke the windows; so that most of the fragments fell harmlessly onto the window-sill or into the rose-bed outside.…That summer, each time I mowed the lawn, the blades of the mower would give a crunch and a shower of sparks when they struck some brown and mangled piece of metal hidden in the grass; these were fragments of the car that had been blown up.”

HEARTH and the Housing Executive

Brett was an energetic public servant, with a particular interest in conservation and social housing. He was the first chairman of HEARTH, a conservation trust and housing association which bought up historic buildings and restored them for use as social housing. The Georgian terraces in Belfast’s markets area were an early HEARTH project.

Hamilton Terrace, Belfast – an early HEARTH project

He later became chair of the Housing Executive, the Northern Ireland housing authority which for a time was the largest landlord in Europe, managing over 200,000 homes at its height.

He felt strongly that public housing authorities should value good architecture and design, “with the conservation of what is best from the stock of the past; with architectural good manners towards its neighbours; and with general respect for the qualities of both the built and the natural environment.”

He was a founder of the Ulster Architectural Heritage Society, serving first as the chair and later as President. In 1986 he became the first chairman of the International Fund for Ireland and he was vice-chairman of the Northern Ireland Arts Council in the nineties.

He published thirty books, mainly on Northern Ireland Architecture, and only retired as a partner in L’Estrange Brett in 1996 (though he continued to act as a consultant until his death). Many of his books are still available, either through the Ulster Architectural Heritage online shop or from good secondhand bookshops.

Although these days he is mostly remembered for his books, Brett was a major figure in public, professional, cultural and artistic affairs in Belfast for five decades. “His interest was always a combination of aesthetics and his left-wing politics,” a HEARTH co-founder said. “He cared about the people who go with the buildings. The past for Charlie was not something to be cleaned and dusted.”