Our grannies’ grannies lived in interesting times. While the main political issue in Belfast leading up to World War I was definitely Home Rule, the campaign for equal votes led some women to launch attacks on Unionist homes and public properties.

The final straw came when Edward Carson, the leader of the Ulster Unionist Party, seemed to promise Ulster women that they would be the first in the UK to get the vote, as part of his plans for a provisional Ulster government. Then he went silent on the matter for months, and only after his London home was besieged for days by angry suffragettes was he forced to go back on his word.

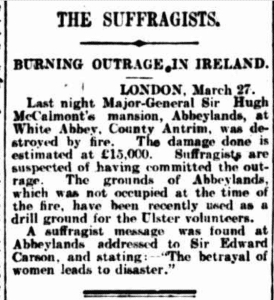

In Belfast, women responded with a campaign of arson and bombing directed at Unionists – even burning down Abbeylands in Whiteabbey, the house where Carson’s Ulster Volunteer Force drilled its troops.

Women’s Votes and Home Rule in Ireland

Women in Ireland had been campaigning for equal voting rights since the 1870s. Of course at the same time, the Irish Home Rule movement was front and centre of politics here.

So for over forty years Irish women asking for equal voting rights in Ireland were basically told to calm down and leave it until Home Rule was sorted out.

But it didn’t mean they weren’t active, but they had to campaign more carefully than their British counterparts. They lobbied Irish MPs to amend the Home Rule Bill with a clause which would have given many Irish women the vote.

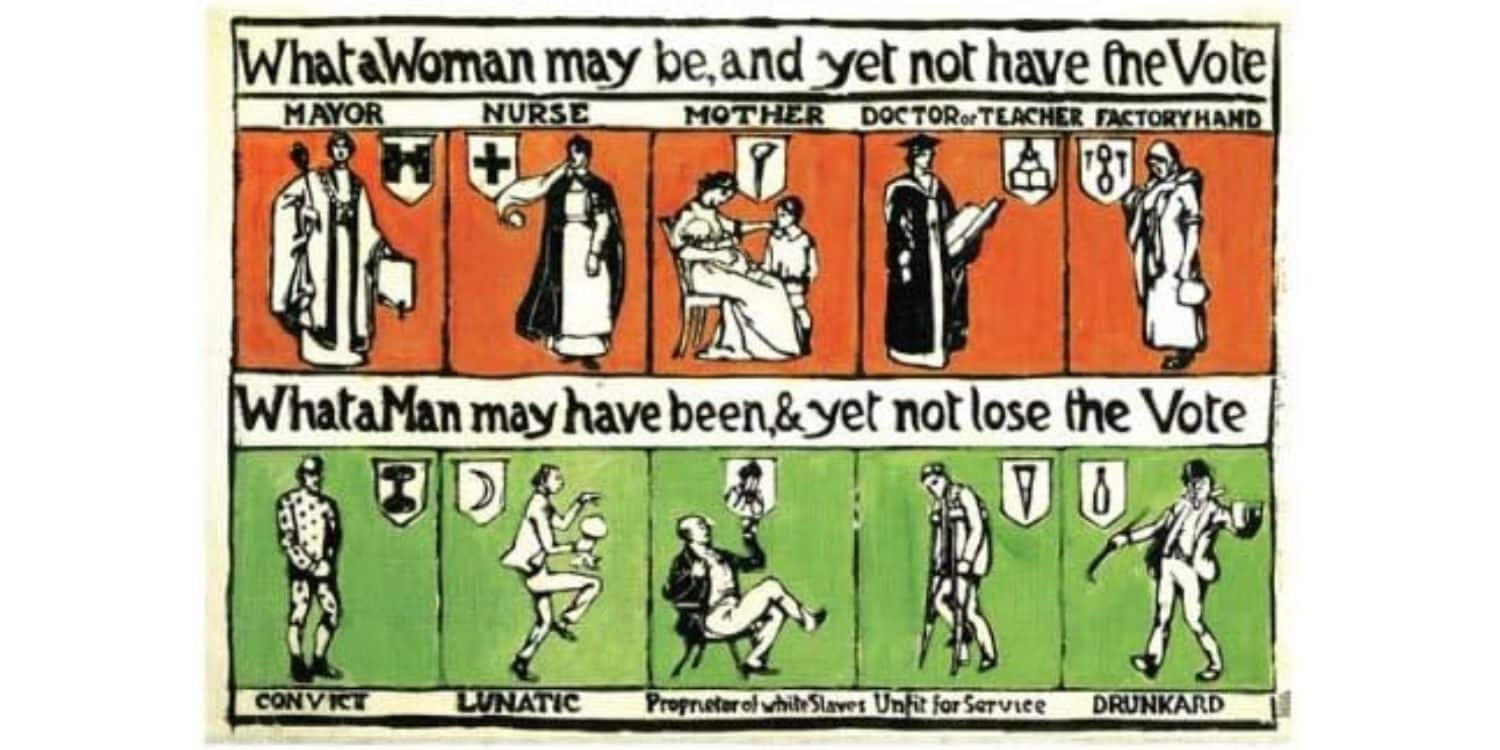

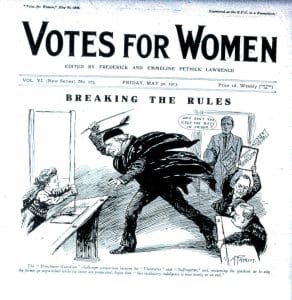

Suffragette poster

The 1910 general election had left the Liberal UK Prime Minister Herbert Asquith dependent on the support of MP John Redmond, leader of the Irish Party – in the same way Theresa May needed the DUP’s support after the 2017 election.

In March 1912 a bill which would have given women across the UK the vote was narrowly defeated. Irish Party MPs voted against it to support Asquith, hoping this would help push the Home Rule Bill through the following month. The Home Rule Bill did indeed pass – but the clause which would have given Irish women the vote was left out.

Suffragists were outraged and a militant campaign began in Ireland. Eight suffragettes broke the windows of government offices in Dublin and were jailed after they refused to pay for damages. When Asquith visited Dublin in 1912 a suffragette even threw a hatchet at him! It was blunt and missed him, but it hit Redmond, grazing him on the ear.

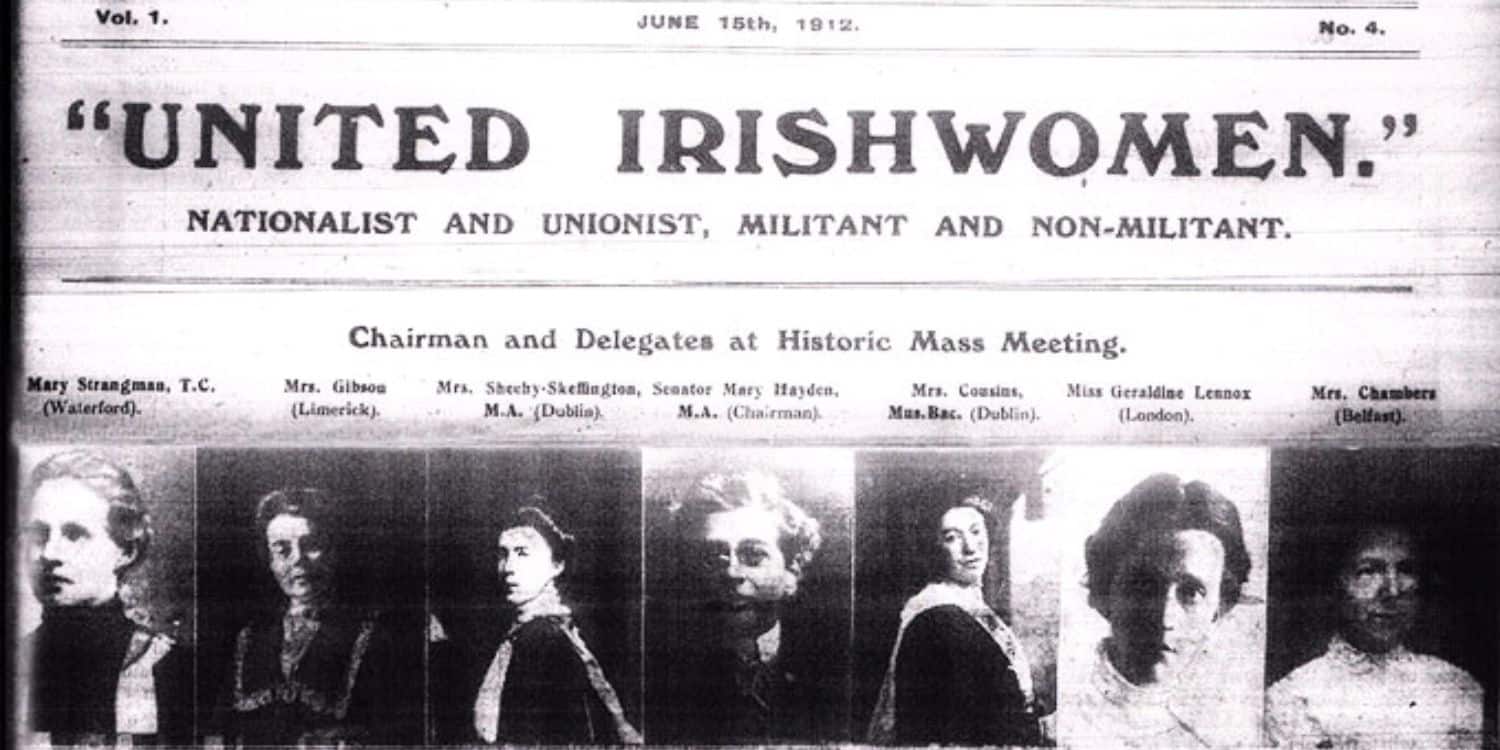

Front page of The Irish Citizen, June 1912, calling for the Home Rule Bill to be amended to include giving women the right to vote

The Ulster Covenant and the Ulster Volunteers

Unionists were even more incensed that the Home Rule Bill had passed, and Carson organised the Ulster Covenant, which was signed by 237,368 men, as a protest against it. Unionist women were allowed to sign an accompanying Declaration, and 234,046 did so.

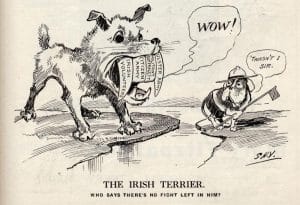

Irish Leprecaun magazine cartoon

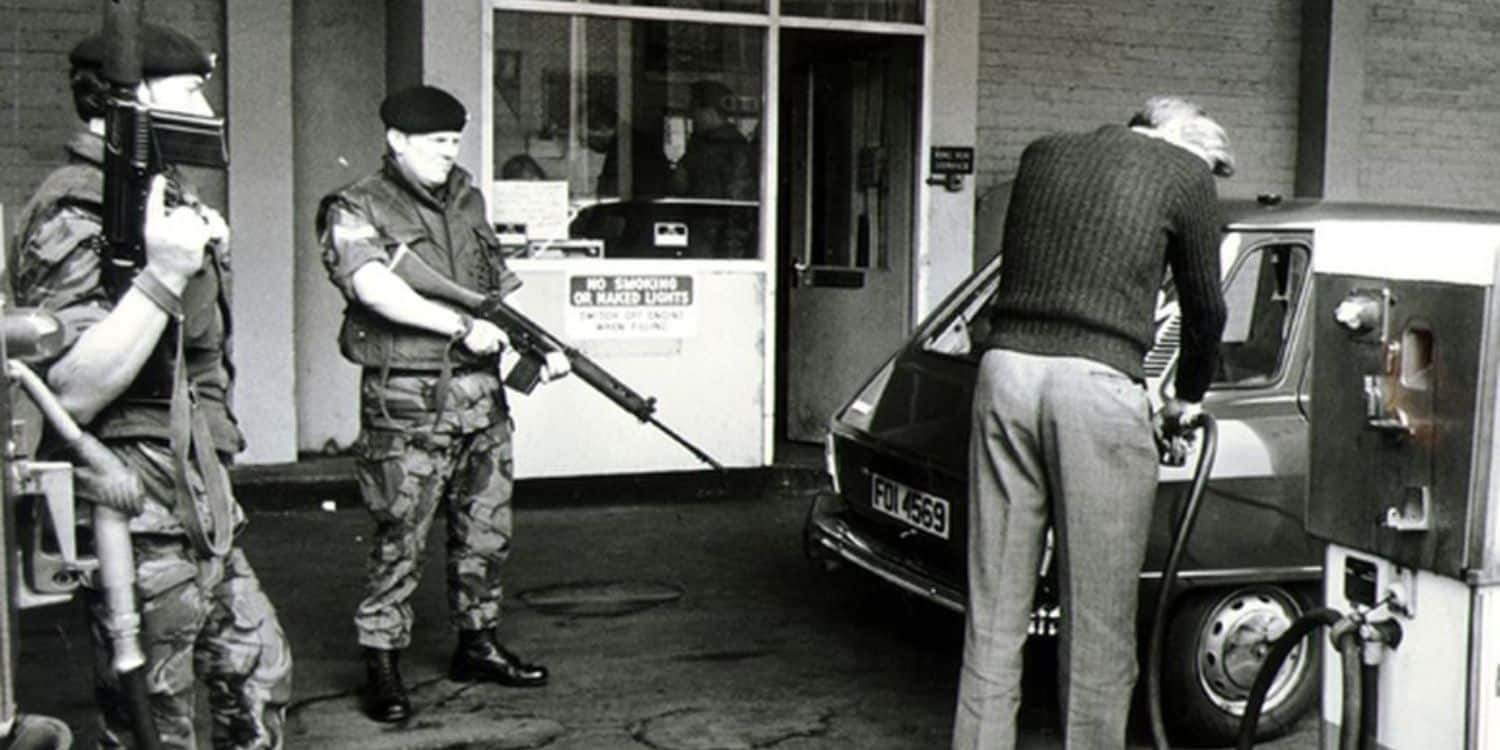

At the same time Carson also established the Ulster Volunteers, the first loyalist paramilitary group. In January 1913 the Ulster Volunteer Force was formed, undergoing military training and buying arms. By April 1914 the UVF was said to have 250,000 members, 24,000 rifles, 5,000,000 rounds of ammunition and 6 machine guns.

The irony that Carson was gun running and threatening the UK with civil war at the same time as he was condemning suffragist violence was not lost on the campaigners or the press. The Manchester Guardian even referred to the militant Unionists as “Ulsterettes”.

An unexpected promise from Carson

In September 1913 Carson drew up his plans for a provisional Ulster government. The Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) saw an opportunity, and announced that they would start a campaign of violence in Ulster unless Carson included women in his government.

Carson was against the idea of votes for women, but perhaps he thought he could appease the suffragettes and keep the focus on the threat of Home Rule. The following day a letter from the Unionist Council appeared in the press which was widely taken to mean that Carson promised votes and government roles for women as part of his plan, giving the women of Ulster what had been denied to the rest of Ireland and making it the first part of the United Kingdom to allow women the vote.

But then there was six months of complete silence from Carson on the matter. Scepticism amongst campaigners grew and eventually members of the Belfast branch of the WSPU, led by Dorothy Evans, held a four day doorstep siege at his London home to force him to clarify his position.

Carson finally emerged to talk to the women, and (rather in the manner of Boris Johnston) had to admit to them that due to disunity within his party, “he was not prepared to give them a guarantee that he would stand out for the rights of Ulsterwomen under the Imperial Government.”

“No friend of women”

At a meeting held in the Ulster Hall on 13 March 1914, Dorothy Evans declared war. “Carson was no friend of women unless he was prepared to stand and champion their rights as strongly as he championed the rights of men” she said. “The civil war that was absolutely certain was the one between the women and the powers that be.”

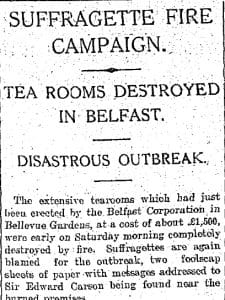

Bellevue tearooms in Belfast destroyed

All bets were off, and in the following few weeks there were twenty pillar-box attacks in Belfast. Attacking pillar boxes (by blowing them up or pouring acid or ink into them) was a highly effective tactic often used by suffragettes. It really got public attention, as the postal service was the primary form of business and social communication, so it was the equivalent of bringing down the internet. By April 1914 the feminist newspaper The Irish Citizen believed that Belfast was experiencing a ‘genuine revolution’.

Attacking pillar boxes was only the start of it. On March 26th, Abbeylands House, the training ground for Carson’s UVF, was burned to the ground. There were several other arson attacks, mainly on unionist owned properties including Annadale House at Galwally and Ballymenoch House in Cultra. Public properties like Knock Golf Club, Newtownards Racecourse and Belfast Bowling Pavilion were vandalised, with acid poured on the greens. The new teahouse at Bellevue Zoo was burned to the ground.

The Carlton cake shop in Donegall Place was a favourite of the suffragettes, as its black and white striped cake boxes provided ‘good camouflage for carrying firelighters.’

Carlton cake shop in Belfast

Windows were smashed at Belfast Town Hall, which at that time was the unionist headquarters, and suffragettes broke into the homes of both James Craig and the Belfast Lord Mayor. The Belfast Telegraph and Newsletter both published articles inciting their readers to take the law into their own hands against suffragettes. In response, a suffragette burst into their offices and slapped their editors’ faces.

On 31st July 1914 they even bombed Lisburn’s Church of Ireland Cathedral. Lady Lilian Spender wrote in her diary:

“I heard about 3 o’clock, what I thought was a big gun firing, but it proved next day to be an explosion caused by Suffragettes, who blew out the ancient east window in Lisburn Cathedral, the brutes. They were all staying with Mrs. Metge, a Lisburn and a most militant lady, and today I believe nearly all the windows in her house are broken.”

Sir Hugh McAlmont, the owner of Abbeylands, received £11,000 compensation from the Belfast authorities. Bishop Henry’s house in Kilroot was also burned down and £20,000 was claimed. In total Antrim had to pay £92,000 in damages to private property owners in compensation for suffragette attacks and the county had to put up rates by 3p in the pound. Of course this did little to endear the suffragette movement to the rate paying public.

Ballymenoch House after the suffragette arson attack

Public backlash

Public opinion against the suffragettes campaign grew as their attacks intensified. When suffragettes heckled the nationalist leader Joe Devlin at a Belfast meeting, one woman was thrown down stairs.

In May the Newsletter reported that a suffragette parade at Belfast Harbour had descended into violence when the suffragettes were subjected to “physical abuse at the hands of irate mill girls”, with Mabel Small having her hat dragged from her head by the crowd who then “pulled her hair, and disarranged her clothing, portions of which were practically torn to tatters.”

There were also reports of two female Austrian tourists on a motoring tour of Ireland being attacked in Ballymena on the suspicion of being suffragettes. Forced to take refuge in a shop, they were eventually rescued by the local UVF commander who escorted them to their hotel.

World War I ends the suffrage campaigns

The escalating violence was only brought to a halt when World War I broke out in July 1914. The suffrage movement then quickly petered out, as most women in Ulster felt it was relatively unimportant compared to the war.

However, the wartime coalition government was more open to women’s suffrage than its predecessor, and the shortage of male labour in factories had proven that women were equally able to do work previously considered to be the preserve of men.

Finally, Votes for Women

In 1918 Parliament finally passed an act granting the vote to women over the age of 30 who were householders, the wives of householders, occupiers of property with an annual rent of £5, or graduates of British universities. About 8.4 million women gained the vote. Later that year another act was passed, allowing women to be elected into the House of Commons.

In the 1918 UK General Election, seventeen women stood as candidates, including Winifred Carney in Belfast. The only woman elected was the Sinn Féin candidate in Dublin, Constance Markievicz (though she didn’t take her seat).

When Ireland gained independence in 1922 they introduced equal voting rights for men and women, but it wasn’t until 1928 that women in Northern Ireland finally had the vote on the same terms as men.

As Emmeline Pankhurst said

“You have not dared to take the leaders of Ulster for their incitement to rebellion. Take me if you dare, but if you dare I tell you this, that so long as those who incited to armed rebellion and the destruction of human life in Ulster are at liberty, you will not keep me in prison.”