Don’t worry, this is not a theological piece but rather a hybrid muse of the historical, social and personal. The churches here are frequently criticised as sources of conflict and division, while others view them as quiet peacemakers who brought spiritual and pastoral care to the bereaved and traumatised. God knows, look across the Belfast skyline and you can see an abundance of them.

From the ornate beauty of Catholic chapels to the plain, but focused, evangelical tin hut gospel halls most of us who were born here have had some experience of our places of worship. Whether this experience is associated with feelings of spiritual serenity, a tedious obligation, or a sense of belonging to a broader community of faith and identity varies massively.

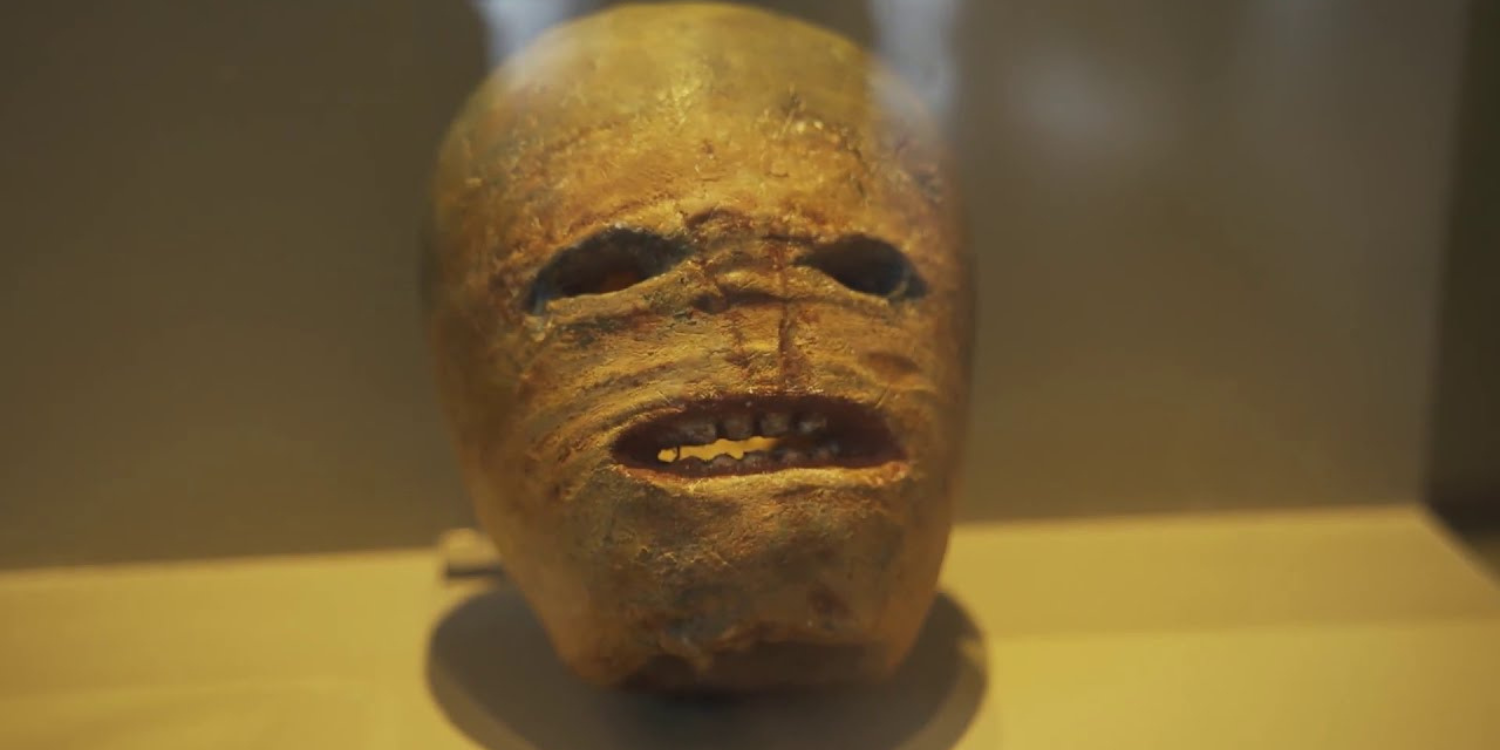

Belfast certainly has a fascinating history of churches. Much is written today of St. Marys in Chapel Lane in Smithfield as the first formal Catholic place of worship in Belfast opened in 1784. Before St. Marys was built their congregation held Mass in secret either in a corner of Friar’s Bush cemetery or in an old Waste House in Castle Street where they had to bring a brick or log to kneel on as the floor was so dirty. The story of how many of the town’s 3,000 Presbyterians and 2,000 Anglicans raised much of the money for 350 Catholic townspeople to build their church in an era of religious tolerance is often told.

The Belfast 1st Irish Volunteer Company, (a Protestant militia raised to defend Ireland when British soldiers were withdrawn to fight in the American Revolutionary War) supported Catholic emancipation. They formed a guard of honour for Father O’Donnell and the parishioners for the first Mass held in St. Marys. The volunteers were led by Waddell Cunningham, the richest man in Belfast, and the same man who proposed unsuccessfully that Belfast establish a slave-trading company just a couple of years later.

In 1954 the construction of the outside grotto that stands today was overseen by Father Bernard MacLaverty. The name rings a bell? – Indeed, his nephew is also Bernard MacLaverty who pens ‘Cal’, later made into the film of the same name starring Helen Mirren. Prior to this he had knocked out (it’s a valid literary term, honest) ‘Lamb’ which in its film version features Liam Neeson with a soundtrack by Van Morrison.

Just across Royal Avenue, or Hercules Lean as it was, and you encounter Rosemary Street First Presbyterian Church. Rosemary street has a complex and fascinating history with three Presbyterian churches practically side by side at one time. The original First Presbyterian meeting house was built in 1695 by Rev. John McBride, the great-great-grandfather of the American author Edgar Allen Poe.

The First church still stands today whilst the others are no longer with us, the Third perishing in one of the four Luftwaffe blitzes of 1941.

Indeed, the church has many links with the United Irishmen, today a blue plaque on the wall of the adjoining Central Hall celebrates it as the birthplace of United Irishman Dr. William Drennan, the man who coined the term “the Emerald Isle” in a poem published in 1815. Drennan’s father was a minister of the church when William was born.

My maternal granny was a life-long church member and we would go there to Sunday school when we stayed with her. In the late 1970s I was stridently admonished by a woman in the Central Hall for shoving pepper up my kid-brother’s nose. I swear but not two weeks ago I saw the same woman and she gave me a filthy look.

Notable congregationalists in the past also include the Harland family of the shipyard, Thomas Andrews, the designer of The Titanic and even the former Alliance Party leader John Alderdice. A famously liberal church (they are non-subscribers rejecting the Westminster Confession of Faith of 1646) they even happily co-exist today with their risqué Rosemary Street neighbours Anne Summers.

St. Patricks Catholic Church in Donegall Street was built when St. Marys could no longer hold the growing Catholic population in the town

He wrote of his youth in the church;

“I stand with my brothers and sisters singing a ludicrous Marian hymn in St. Patricks Church at evening devotions” and describes a British military band marching by with young soldiers in formation destined for the docks then onto India, predicting many will never return.

Commenting on both gender and social conditions Moore wrote;

“Inattentive and bored I kneel at Mass amid the stench of unwashed bodies where eighty percent of the female parishioners have no money to buy overcoats or hats and instead wear black woollen shawls which cover head and shoulders marking them as ‘Shawlies’, the poorest of the poor.”

St. Georges Church of Ireland on High Street has seen a church in many forms on the site going back to 1306 and no doubt before, when it

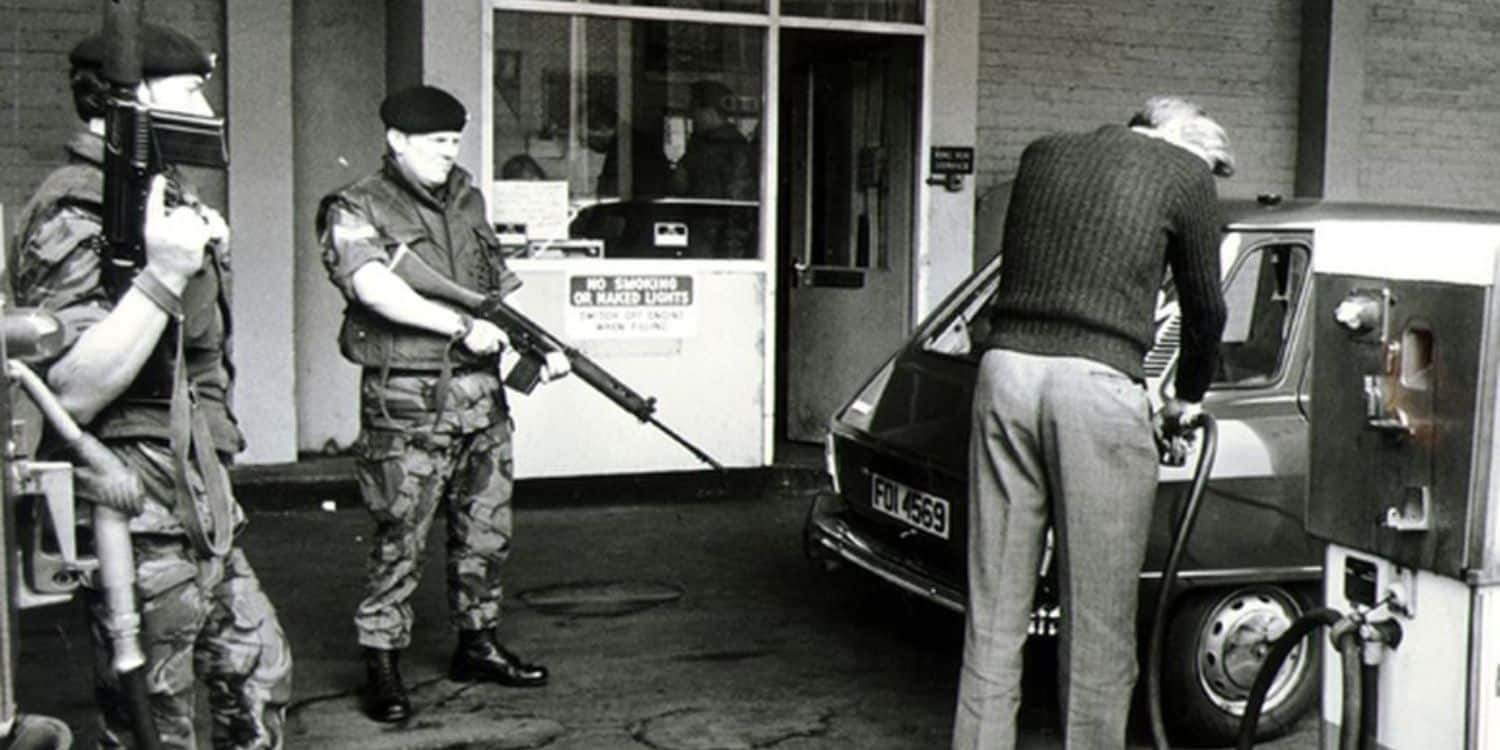

But in 1649 Cromwell’s troops, those supporters of regicide, took it over, stripped lead from its roof to make musket balls and stabled their horses inside. Yet by 1690 King Billy is sitting in the same place enjoying a church service dedicated to him, with first the church and then the monarchy restored and being fought over by Catholic and Protestant forces across the island.

I’ve barely scratched the surface and we could travel and unravel so much more of our churches’ histories, but hopefully I’ve given you a flavour of their rich stories. And if I have piqued your interest or curiosity you can find out more on our Best of Belfast Walking Tour or even in one of our Self-Guided Audio Tours where the churches feature along with so much more.