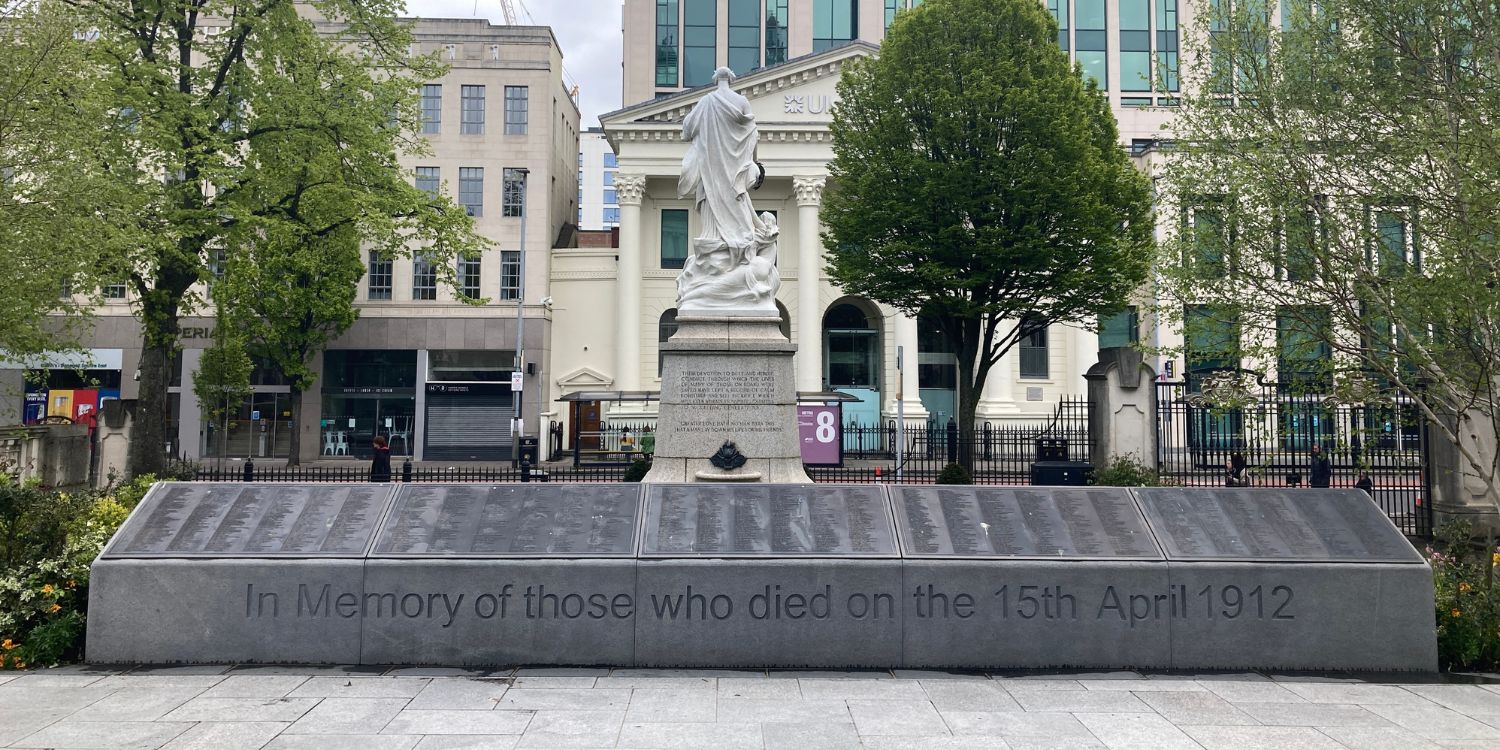

A few weeks ago I was waiting to start one of our tours in the grounds of Belfast City Hall and I had a bit of time on my hands, so I ended up in the Titanic Memorial Garden which sits on the east side of the grounds.

I was looking at the memorial plinth, which lists all the victims of the sinking of the Titanic in alphabetical order. And I noticed that two names had asterisks beside them.

A little detective work told me that the asterisks denoted names that researchers could not find any record of – they had been listed as casualties by the White Star Line but didn’t appear to exist anywhere else. And that got me thinking – with so many passengers and so few bodies recovered, how sure can we be of all their identities?

Memorialising all the victims – a Titanic undertaking

The Titanic sank in the North Atlantic on 15th April 1912, and of the estimated 2,224 passengers and crew aboard, more than 1,500 died – the deadliest sinking of a single ship up to that time. Only 337 bodies were ever recovered. Some sank with Titanic, and winds and currents quickly scattered the remainder.

So with some passengers travelling under aliases and others selling their tickets on, trying to memorialise each victim was always going to be an impossible task. But in 2012, a century after the sinking, Belfast City Council attempted to do just that.

The opening ceremony of the Titanic Memorial Garden on the centenary of the sinking in 2012

The Titanic Memorial sculpture

The plinth that lists the names stands between the City Hall and the original memorial statue, which commemorates local victims of the disaster.

It’s a marble sculpture of a woman (Thane, who represents either death or fate) holding a wreath over the head of a drowned sailor who is being raised above the sea by two nymphs.

It was designed by the English sculptor Sir Thomas Brock, who also created the statue of Queen Victoria at the front of the City Hall. It was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1916, but because of World War I it was not unveiled in Belfast until June 1920.

The original site of the Titanic Memorial

The memorial is 22ft high (apparently in honour of the 22 local men who died on the Titanic) and features small bronze water fountains in the shape of gargoyles and inscriptions around the plinth. The local victims are listed by rank, starting with Thomas Andrews, the ship’s architect and managing director of Harland and Wolff.

Originally, the memorial was located in the middle of Donegall Square North, between the City Hall and Robinson & Cleaver, but drivers travelling around the square often didn’t see it or couldn’t change lanes in time, and after multiple traffic accidents it was moved to its current location in 1959.

The memorial had to be moved as cars kept crashing into it.

It was restored in 1994 and then again in 2012, to coincide with the opening of the memorial garden and the Titanic centenary. At this point, the memorial plinth was added – 30ft wide, it bears five bronze plaques naming 1,512 casualties in alphabetical order. It was the first Titanic memorial in the world to record all the victims on one monument.

Mistaken identities

But actually there are 17 names too many on the plinth. Some are survivors mistaken for victims and some are misidentified or unlisted passengers or crew.

James Bull, James Callahan, William Edmunds, Mr S Halloway, Mr R Morrell, Mary Lennon, Mr W Nathan, Robert Reeves, John Rice, Frederick Roberts, William Taylor, Mr A Watson and Mr Watt either never sailed on the Titanic or are listed elsewhere under their correct names.

Miss Berthe Leroy and Mr Fahim Ruhanna Zenni actually survived the sinking, so they shouldn’t be listed either!

And then there are the two names with asterisks against them – John Horgan and Thomas Hart. A Limerick man called John Horgan bought a third class ticket to sail on the Cymric on 7th April 1912, but when that sailing was cancelled his ticket was transferred to the Titanic.

Senan Molony, who wrote “The Irish Aboard Titanic” speculates that he sold his ticket on to someone else – most likely Timothy O’Brien, another Limerick man who was lost on the Titanic but does not appear on the passenger list.

The Thomas Hart mystery

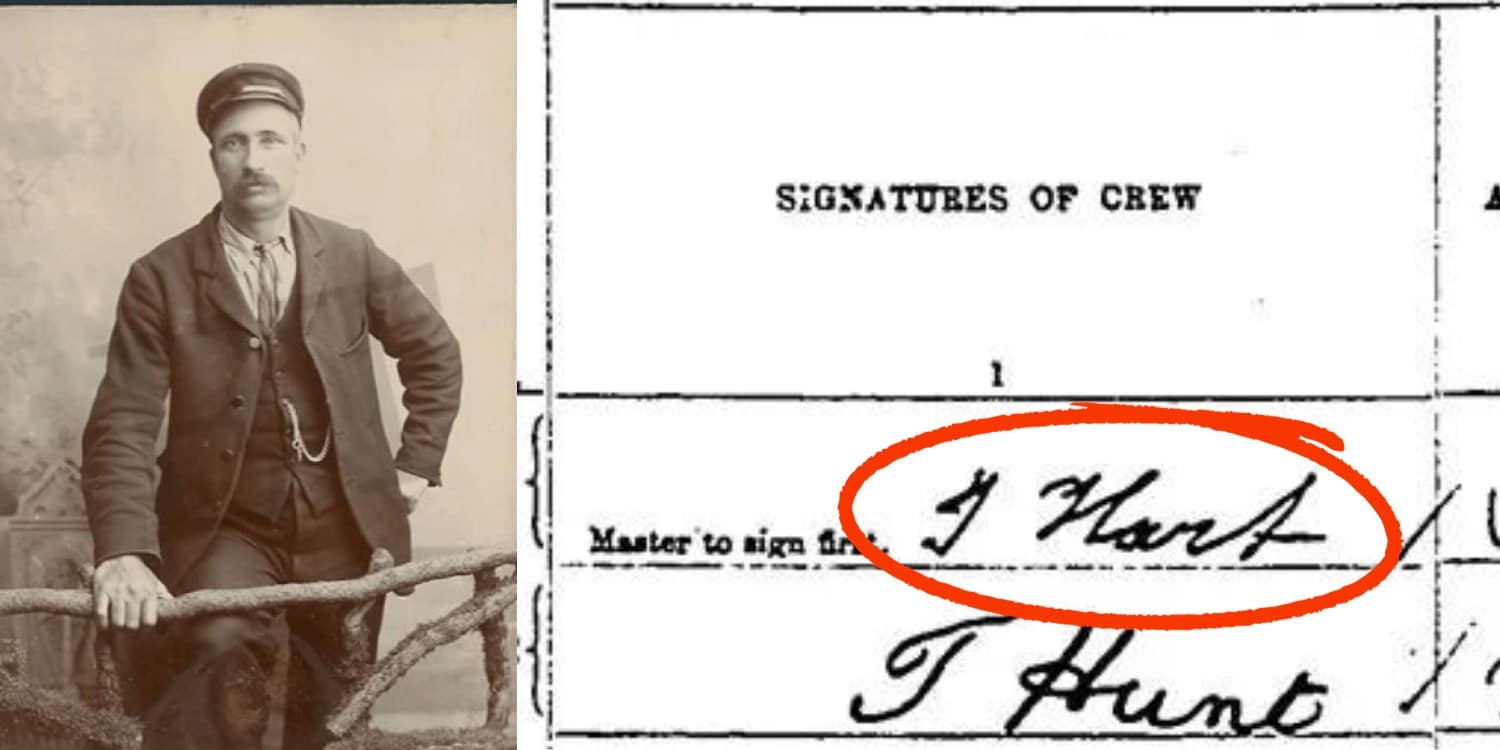

The other asterisked name is Thomas Hart, and there is quite a story behind him. A fireman from Southampton called James Hart was lost on the Titanic and he is also listed, correctly, on the plinth.

But when the White Star Line transcribed the ship’s manifests immediately after the sinking, they recorded his name as T Hart rather than J Hart – the handwriting style means it would be an easy mistake to make.

Not a T but a J – A photo of James Hart and his name as it appears on the Titanic manifests.

By coincidence, there was a Thomas Hart from Liverpool who was also a ship’s fireman, and his mother only knew that he was away at sea at the time the Titanic sank.

She had already lost her husband (also a ship’s fireman) to drowning so when she read the list of casualties and saw “T Hart, Fireman”, she assumed the worst.

The Titanic Relief Fund

The sinking of the Titanic prompted huge public donations, with the London Lord Mayor’s Mansion House fund alone raising over £414,000, and the Titanic Relief Fund was founded to support widows and dependents of the Titanic’s crew.

Some families were given weekly allowances, and the support was split into tiers according to rank, with the widows of officers and engineers getting £2 0s. 0d and each child awarded 7s. 6d.

Firemen were at the bottom of the list, with widows receiving just 12s. 6d and children 2s. 6d. Thomas was unmarried, so his mother would have been able to apply for support as his dependant.

Thomas comes back from the dead!

She engaged a firm of solicitors to try to establish whether she would receive compensation. But a few weeks later Thomas returned home from sea safely!

Once she had recovered from the shock of her son coming back from the dead, she got back to the solicitors to tell them he was no longer missing. Possibly to avoid looking like a gold digger, she also told them that his Discharge Book (basically his ID card) had been stolen.

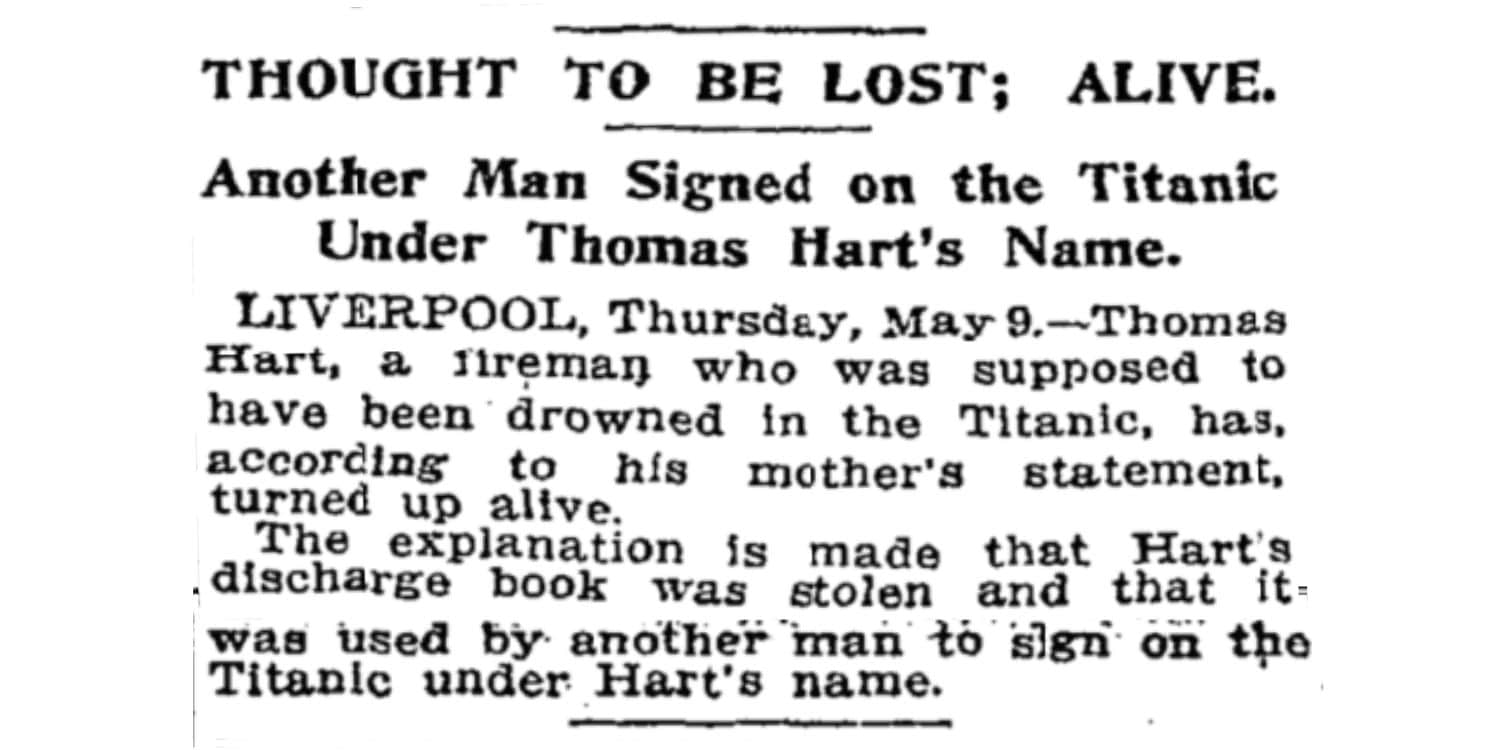

The Merseyside Daily Post first reported the story quite drily on the 8th May 1912:

Messrs. Quilliam, of Liverpool, solicitors, acting on behalf of relatives of Thomas Hart, marine fireman, of Liverpool, supposed to have been lost in the disaster, have been informed by his mother that her son has turned up. He told her that he had had his discharge book stolen from him. Someone evidently signed on the Titanic with Hart’s name and credentials, and it was he, and not Hart, who was drowned.

But the story was then picked up by the New York Times on 9th May 1912, and they put a more sensational spin on it:

Clearing James Hart’s name

This was the story that stuck for years, with further embellishments added later – that Thomas had signed up to the ship, but just before the Titanic’s departure he drank himself unconscious. He came to only to find both his Discharge Book and the Titanic gone. Hart was so ashamed of his behaviour that he did not return home until he learned that he had been reported lost with the ship.

This story caused so much grief for James Hart’s family (because the implication was that James had stolen Thomas’s Discharge Book) that they had this statement published in the Southampton Times and Hampshire Express on May 18th, 1912:

LOST FIREMAN’S VINDICATION

That there was a man named Hart on the Titanic there is no doubt. J. Hart of 51 College Street, attached his signature to the ship’s articles, and the inference was that he had sailed under false pretences. The suggestion that he used another man’s book has given intense pain to the members of the family, who indignantly deny the statement.

Mr Hart has sailed out of Southampton for over twenty years. He served the Union Castle company and the R.M.S.P. before transferring to the White Star Line, and we are assured that his discharge book was a good one. There was, therefore, no reason why he should hide behind another man’s character, and that he made no attempt to do so is proved by the fact that he gave his College Street address when signing on. Had he assumed the name of the Liverpool man, he must also have given the Liverpool address of that fireman. J. Hart was a member of the British Seafarers’ Union, and we have been asked by the members of his family to publish their facts in order that the dead might be vindicated.

So Thomas Hart never sailed on the Titanic. In fact, he lived on for another quarter of a century, dying on March 5, 1937 of broncho-pneumonia, aged 56.

Our Best of Belfast and History of Terror tours both start right beside the Titanic Memorial Garden, and the Best of Belfast tour finishes there too. So if you have a few moments, take a look at the names on the plinth – behind each one there’s a story, though perhaps not all as curious as Thomas Hart’s.