Let’s face it, Belfast is a bit odd. Thanks to the Troubles it’s an unusual place for visitors; alien and yet familiar, regardless of whether you’re from Britain or the South.

The conflict and its memories are omnipresent in the inner-city communities where so much of the violence took place, with literally thousands of murals and memorials scattered like confetti across the map.

But the city centre is different. As we visit the locations of major attacks and events in the city centre, guests on our A History of Terror tour quickly realise there are no memorials at any of the sites. New buildings have replaced the old and thankfully the ring of steel is long gone, but there’s practically nothing to commemorate the victims.

When asked about this absence, we’ve always said that our government and those who invest in the city find it difficult to agree on how to commemorate our uncomfortable heritage and instead focus on presenting the ‘new’ Belfast to visitors.

Or maybe the hope is that we forget that over 70 people were killed in the city centre alone, including civilians, security forces and paramilitaries. There were hundreds of bombs and thousands of casualties.

And if we did erect memorials, who deserves to be remembered?

If we start putting up memorials and commemorative plaques in the city centre, where would we stop? You wouldn’t be able to walk 10m through the centre of town without seeing another plaque, and then another. Would that help us celebrate the end of the violence and bring us together, or could it simply rekindle memories of fear and terror and harden the hate? So the easy answer is to have little or no memorialisation in the shared and neutral space of the city centre.

There is in fact a small and subtle ceramic plaque in the Laganside Bus Station commemorating bus company employees, including

Except that there is a memorial. A memorial wall to be exact, but it has been forgotten – whether deliberately or accidentally, we don’t know. While poppies, lillies or wreaths are laid annually at memorials across the country, there’s no annual remembrance or ritual commemoration that we know of, even though it remembers the first 1,500 victims of the Troubles without judgement.

But where is it? Well, it’s hidden in plain sight – practically facing the Albert Clock in Jubilee Square on Victoria Street.

From a distance it looks like a bricked-up doorway in the old perimeter wall of St. George’s Church. For a few years we led our walking tours right past it, never realising its significance – until one day we walked a little closer and realised what it was.

It was commission by the the Irish Congress of Trade Unions (ICTU), designed by the famed Dublin artist Robert Ballagh, (who also sold Phil Lynott of Thin Lizzy his first bass guitar!) and created by the Irish ceramicist Stephen Pearce.

Ballagh had previously painted a number of pictures depicting the violence of the Troubles. The memorial wall however is more abstract – a mosaic of green and brown terracotta numbered tiles in a variety of sequences, but ultimately listing every digit from one to one thousand five hundred.

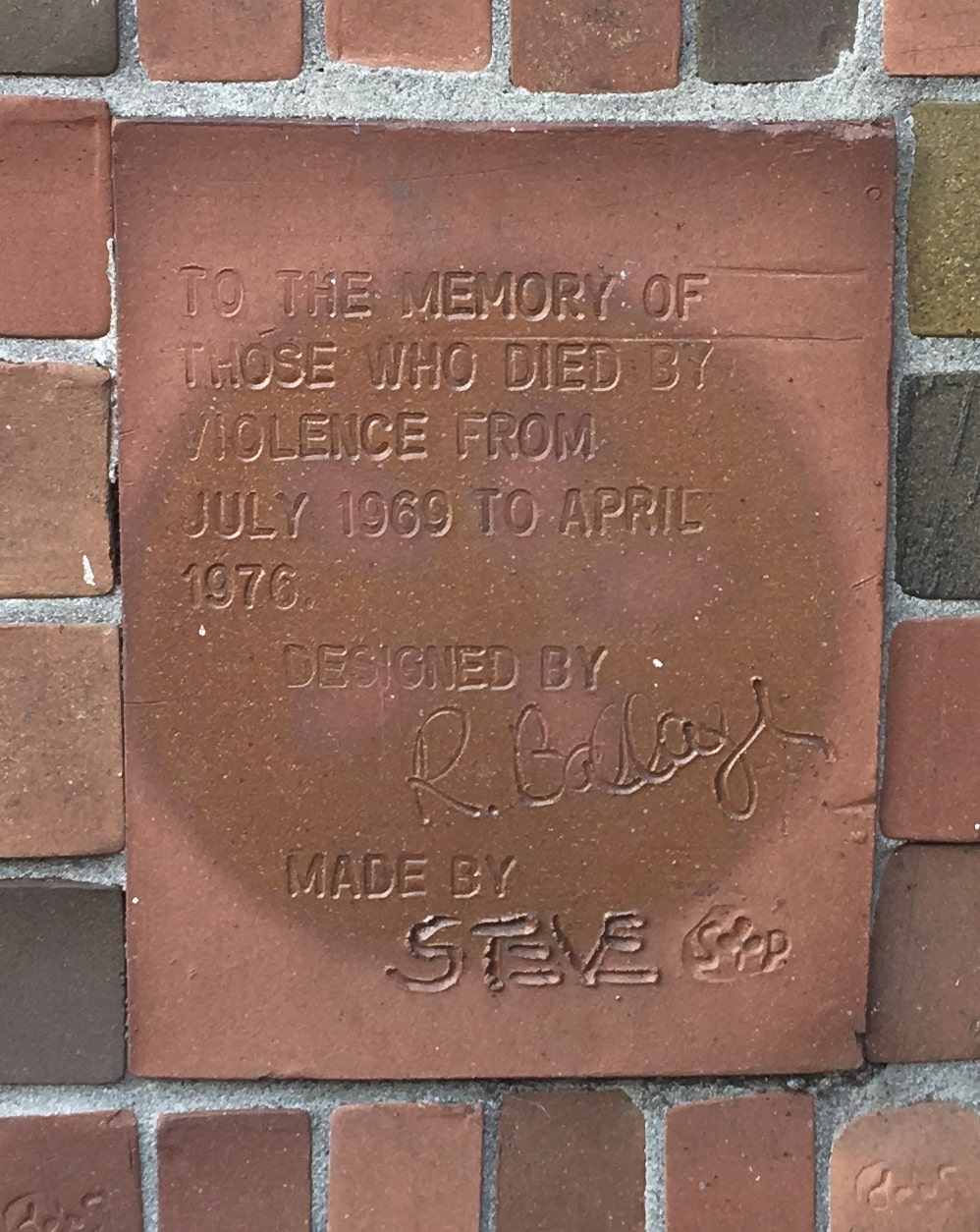

The dedication in the bottom right hand corner reads:

“To The Memory Of Those Who Died From Violence From July 1969 To April 1976.”

Designed By Robert Ballagh

Made By Steve

It’s certainly not the most striking of memorials and conveys no overt emotion, but maybe that was part of the concept – to keep it simple and factual, and maybe even dispassionate. Don’t give anyone a reason to take offence, simply list the dead numerically and anonymously, where every one is equal.

1,500 dead on 2m².