Sir Walter Devereux 1st Earl of Essex may not be as (in)famous as Sir Arthur Chichester, the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell or King William of Orange amongst those to visit Ireland and leave an indelible historical mark on the land, but he certainly deserves a mention.

Obviously from an aristocratic line, Sir Walter was among the second wave of Elizabethan nobles who sought to ingratiate themselves with her Majesty and personally benefit from the colonisation of rebellious and troublesome Ireland. This was the era of global expansion by England, Spain, France, and Portugal.

England, as ever, was seeking to deal with its smaller Catholic, Reformation-resistant neighbour on its terms, with a clear eye on the bigger politics of Europe. The province of Ulster continued to be particularly troublesome and rebellious, and despite negotiations and deals with the local leadership, many in England felt a more robust policy was needed – a policy of land acquisition without recompense and the expulsion of those who had worked there under the previous owners.

Essex, who had already been rewarded for his role in quashing the supporters of Mary Queen of Scots was a confident man and offered to subdue and colonise parts of Ulster initially at his own expense. He mortgaged his estates in England and Wales to the tune of £10,000

Sir Brian MacPhelim O’Neill with whom England had been doing business previously (he was now Lord of Lower Clandeboye for his services against the rebellious Shane O’Neill) warily welcomed Essex (despite a formal handshake and statement of goodwill) and couldn’t help but wonder why he had arrived with a thousand troops? His suspicion was justified when Essex swooped, taking custody of ten thousand of O’Neill’s cattle. Guards at Carrickfergus castle were bribed into releasing them and Sir Brian successfully ran them to Massereene in County Antrim with Essex in pursuit.

Morale amongst Essex’s forces was low by winter, but encouragement was given to Essex and his men in 1574 when he was bestowed the title of Governor of Ulster by the Queen. To celebrate, he then turned on his own demoralised forces, hanging a group of Devon men as punishment for attempted desertion and imprisoning officers who had shown a degree of friendship to O’Neill.

With discipline restored he then pursued another local leader Turlough Luineach O’Neill. Entire crops were torched in the Blackwater and Clogher Valleys in pursuit of Luineach to Derry. A band of Turlough’s followers were discovered seeking refuge on a river island near Banbridge and slaughtered. Another 1,200 cattle were taken. All this was undertaken without any actual military engagement with opposition forces.

However, a truce with Sir Brian MacPhelim O’Neill was finally agreed. In October 1574 Essex and his men were invited by Sir Brian to a celebratory feast at Belfast Castle. (These events were quite the occasion, comparable to a long weekend in Laverys Bar in the 1990s, but without a break for a baked potato from Spudz, because they hadn’t been discovered yet). Records show “they passed three nights and days together pleasantly and cheerfully…..they were agreeably drinking and making merry..”

Until the moment when the forces of Essex seized O’Neill, his brother and his wife. Then, in front of him, all of O’Neill’s people were slaughtered, – men, women, youths and maidens. – – There’s some inspiration for an episode of Game of Thrones right there!

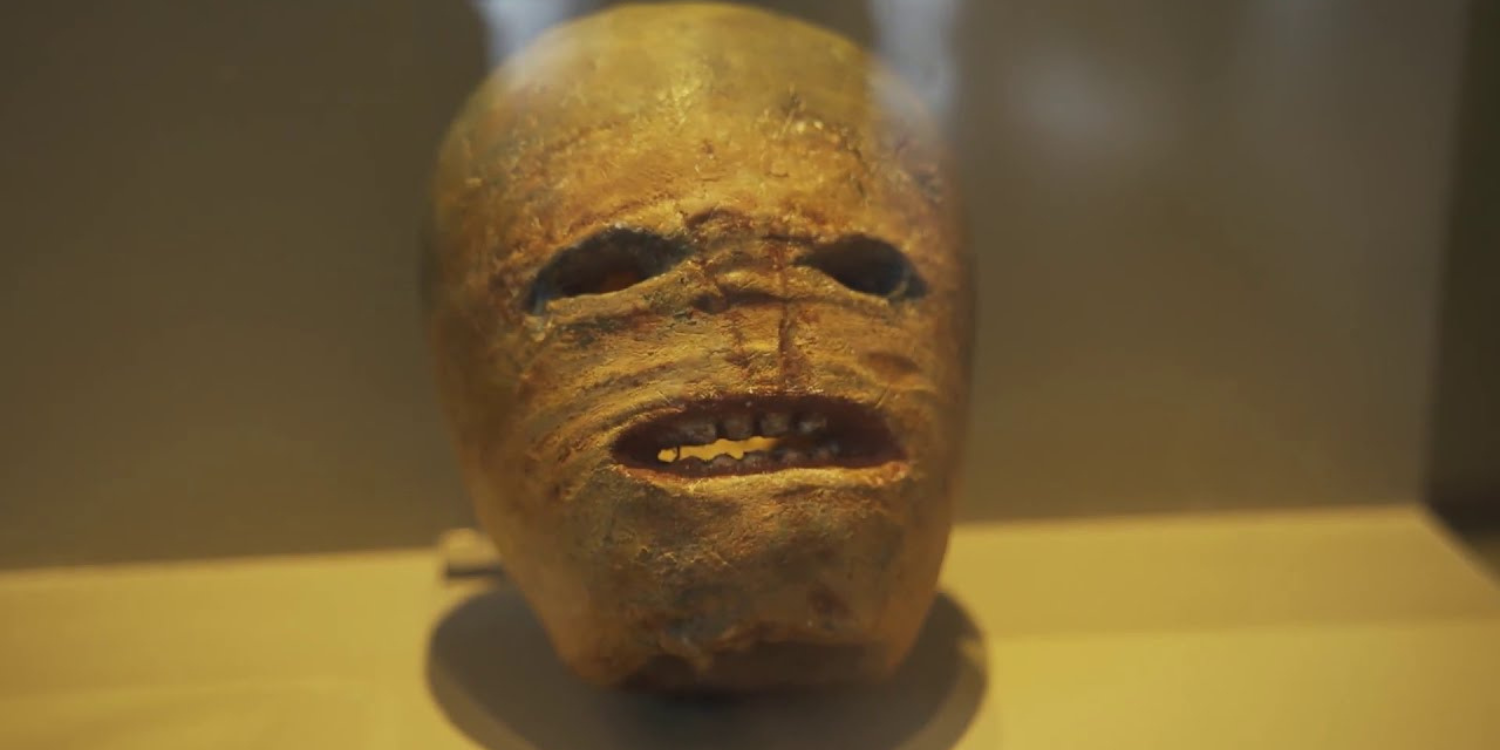

To ensure the message to the native Irish was crystal clear, O’Neill, his wife and brother were then transported to Dublin where they were executed and quartered for maximum impact.

With the tone truly set, Essex then committed another act of barbarity in July 1575 on Rathlin Island off the north coast of County Antrim. Sorley Boy McDonnell was an astute Scots Gael, building around him a strong network of forces through negotiation and inter-marriage.

An initial raid to capture the island failed, and so frigates and other vessels sent from Carrickfergus spent a four-day siege pounding the wooden ramparts of the castle with “red hot cannonballs.” Eventually on 26th July the besieged negotiated surrender on the condition that the hundreds of civilians inside were spared. Essex could not be trusted though. 200 Scots soldiers loyal to Sorley Boy were slain and then up to 400 civilians including many women and children were slaughtered. Those who had taken refuge in caves and cliffs around the island but were relentlessly pursued until discovery and death. One of the two naval officers in charge was Francis Drake.

In a letter to Queen Elizabeth, Essex justified the massacre stating that his men had been incensed by the casualties and fatalities they had endured during the initial assault and demanded revenge. Sorley Boy McDonnell wasn’t in the camp but witnessed the events from a distance. He was said to have danced and howled with grief.

Sir Walter’s life and career was to take further twists and turns. He returned to England in 1575 saying he basically wanted a quiet life with no more adventure. It must have been very tiring after all, uniting a whole region of Ireland in rage against him. However, the Queen still favoured him and managed to persuade him to take the post of Earl Marshal of Ireland.

At the celebratory feast of this event in Dublin Castle in September 1576 he fell ill and died three weeks later. Officially his death was recorded as dysentery (a bad pint in those days) but a suspicion lingered he was poisoned at the behest of Robert Dudley, the Earl of Leicester who had grown ‘close’ 😉 to Walter’s wife, Lettice, while Essex was away in Ulster, and went on to marry her in secret after his death.

Whilst some of this is written slightly whimsically, serious issues and events are being highlighted. The nine years war was to follow, the plantation of Ulster was to ensue, the Chichesters were on their way, and the rest is history….