The DC Tours phone rang on Monday, and I answered professionally and courteously as usual. Nadia, a pleasant woman with a posh London accent, quickly explained that BBC Breakfast wanted to interview me as a Belfast tour guide and historian about the Kenneth Branagh film ‘Belfast’.

“You have seen the movie, haven’t you?”she asked, I explained I hadn’t yet. My big son and I had intended going on Saturday afternoon but opted instead for the footballing inferno of passion and skill that is Glentoran versus Warrenpoint at The Oval. Seemingly undeterred by this gibberish, Nadia persuaded me to trot down to the Odeon to watch the film at the first available showing, and then meet the BBC crew at the site of Branagh’s childhood home in Mountcollyer Street, North Belfast the next morning for the interview.

“I’m not going to like this“ I thought. I steeled myself in anticipation of something sugared, sanitised, possibly even verging on a sickly disservice to those forced to flee in August 1969 and in the subsequent years.

So how come my initial reaction was one of pleasure and enjoyment? Pleasure and enjoyment that has increased in the 48 hours since I walked out of the cinema to the point that I’m writing about it now.

First point. I’m no Barry Norman, but visually I loved it. The black and white worked for me. I had heard people criticise this though I’m not sure what their take was. Art is subjective isn’t it and my subjectivity liked it for not very sophisticated or intellectual reasons. I just thought it looked good.

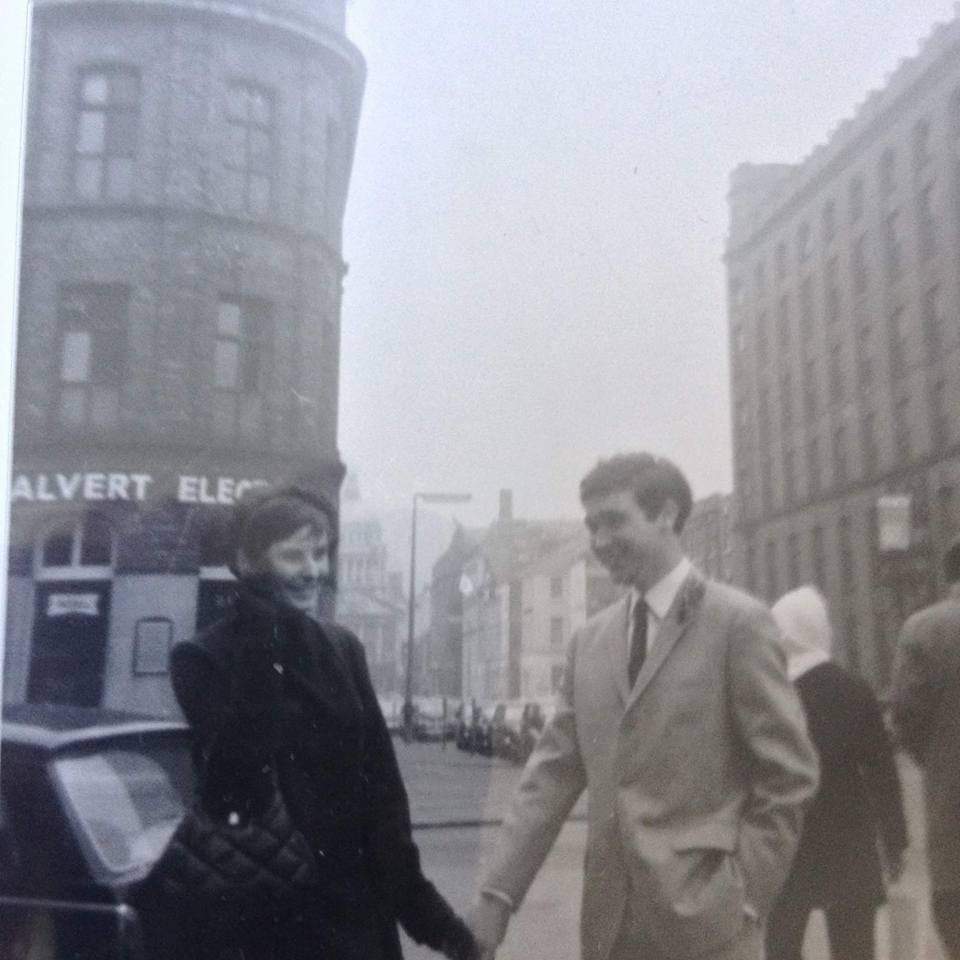

The parents were too glamorous for working class Belfast people I’d heard people say. Yes, Jamie Dornan and Catriona Balfe are both popular in the attractive people stakes but we aren’t a city entirely populated by the facially challenged. The clothes weren’t exactly Mary Quant-esque and the grandparents were absolutely typical of their generation in their appearances. I have a photo of my ma and da in

The trailer featured the dance and song scene as the da serenades the ma with ‘Everlasting Love’. Boke I thought in advance. Then I saw it in its full context. After the grief of a funeral people often cut loose from their grief with booze, song and dance. Love for those remaining after death can be expressed in ways we mightn’t normally employ in everyday life, even among dour Belfast Presbyterians, and hey – some of us enjoy a drink. Plus if you follow the dialogue you’ll notice the after-funeral bash is in a social club. I like that. I like funeral parties in social clubs.

I would also argue this too – the scene is stylised but it’s through nine-year-old Buddy’s eyes. Many nine-year-olds are in the last stages before their ma and da singing and dancing becomes mortifying. At nine you still tend to think highly of them and nine-year-old Buddy reveres and loves his parents as they do him. There’s plenty of time for family shite and conflict on down the line. He thinks they look and sound brilliant.

But here’s the the nub of my reaction. I nearly wanted to dislike it before I saw it. Intellectually, morally and politically it was going to be the antithesis of what I do. On our History of Terror tour we examine violent events. We researched them extensively. We put them in historical context, we detail the actualities, the human stories of perpetrators and victims and those who were both. We outline the immediate impact then dissect the torturous legacies we live with today, even after ceasefires, negotiations and the Good Friday Agreement. It’s exhausting. Suddenly looking through the eyes of a nine-year-old is a relief and a release and yet still a learning tool.

Then after I thought even more. The film is about memory as well as relationships and conflict. What do we do in this place on a daily basis, on an annual basis, in our heads, on our streets and our walls? – We doggedly remember and commemorate. 12th parades, Somme parades, Easter parades. Those are the big ones. Add to that the parades and commemorations that have been born and grown since the 1960s and on. Annual parades for the hunger strikers, annual parades for Brian Robinson. Band parade competitions. RPG Avenue, Freedom Corner and a plethora of thousands of other murals about our past(s).

We place flowers on lampposts on anniversaries of deaths and attacks. We have memorial gardens for our organisations. We remind ourselves constantly of our traumatic experience and the narrative to tell others what happened. One mural on The Newtownards Road tells us we have a duty to speak for the dead.

This is all perfectly legitimate, and we are not the only society that does it but we are arguably one of the most proficient at these forms of remembrance. Whilst I believe it is legitimate and for many a political and emotional necessity, I’m also finding it exhausting too. It can make place and space ominous and overpowering. How long will we do it for?

So here’s where I am after looking at 1969 through nine-year-old Buddy’s eyes. I’ve been feeling slightly lighter within myself for two days

Jude Hill as Buddy was delightful, Ciaran Hinds was superb as usual, even Dame Judy’s Belfast accent was better, most of the time, than I thought it would be. Yes, none of the houses depicted had a flag holder but I’ll get over that even if it irked me more than it should.

There’ll be plenty more films, TV dramas and documentaries to rigorously post-mortem these times but for now I’m content that ‘Belfast’ was how it was. I’m happy to write that.