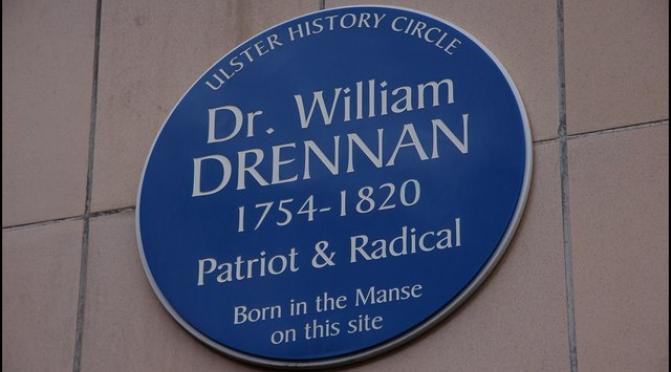

As you leave TK Maxx with your flawed but cheap jacket or Ann Summers with your perfect but expensive lingerie scan your eyes along the front of our old friend, Rosemary Street First Presbyterian church, to the Central Hall beside it. There you will see a historical blue plaque to an intriguing Belfast man, Dr. William Drennan. A man of political agitation and organisation, a letter and

Born in 1754 in the church manse where the central hall now stands, Drennan was one of 11 children, but incredibly only three survived beyond infancy. One of those was his sister Martha (later McTier) who much of William’s life and work was entwined and interdependent with.

Drennan is best known to many for his founding role in the Belfast Society of United Irishmen founded in Peggy Barclays Tavern in October 1791. Whilst names such as Tone and McCracken become synonymous with the society and particularly the 1798 rebellion, Drennan too was a key figure.

He drafted their ‘Test’, which members of all persuasions swore when committing to their “brotherhood of affection.” This was to

The French Revolution was welcomed by Drennan and his peers but as correspondence between him and his siter Martha clearly illustrates, by 1792 they had become disillusioned and repulsed by the increasing violence of the new regimes in revolutionary France, – “I am quite turned against the French.”

By the time the United Irish had embraced revolutionary violence as being unavoidable, Drennan had effectively disengaged from it. Many of his erstwhile friends and peers were hung in the aftermath of 1798, and Drennan too suffered to a lesser degree as the obstetrics practice he established in Dublin was shunned by many due to his previous associations and activities. Nevertheless, Drennan remained loyal to the ideals of the United Irish and went on to write letters and pamphlets against the 1800 Act of Union.

Drennan was a pioneer in other fields outside politics, a man ahead of his time. Several examples stand out and one is so relevant today it is intriguing…

In 1782 as a visiting physician to the Belfast poorhouse Drennan proposed the use of a smallpox variolation to combat the brutal disease that killed so many and blinded and mutated survivors with scars. Variola was the smallpox virus and variolation involved powdered smallpox scabs being rubbed into deliberate skin nicks. Symptoms of the disease developed in the recipient for up to four weeks before ceasing as immunity developed. The practice originated in China and India and its introduction to Europe and North America in the 17th century was often met with social and political opposition.

The following decade saw British physician Edward Jenner develop the first vaccine to be used against smallpox, using the safer cowpox in the process. By the 1830s the smallpox vaccine was meeting organised opposition by figures who also campaigned on other aspects of social legislation such as the Poor Law of 1834.

As a footnote, the World Health Organisation conducted a global smallpox vaccination campaign from the 1950s to the late 1970s which saw smallpox, outside laboratory conditions, eradicated. Interesting huh? – And there’s our William advocating its predecessor in Belfast over two centuries ago…

As referenced earlier, obstetrics was his medical field whilst his sister Martha was an advocate and organiser for women’s health. In

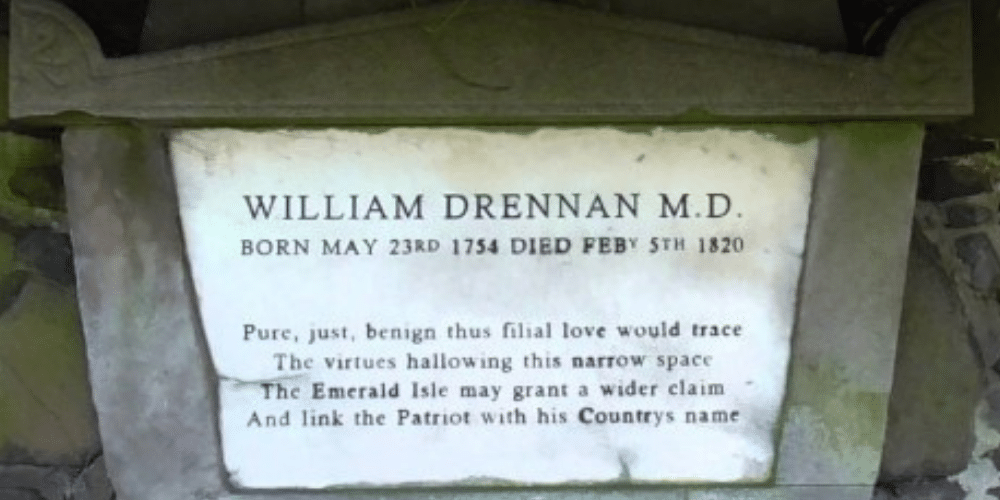

A fine example of the creative nature and legacy of Drennan is from his literary endeavours. The phrase ‘the Emerald Isle’ in reference to Ireland is universal. It’s used in everyday life as frequently as many of William Shakespeare’s phrases, but who first coined it? – Drennan of course! ‘The Emerald Isle’ first appears in print on the pages of Drennan’s poems of political rebellion, specifically – ‘When Erin First Rose’ in 1795. Not bad, eh?

Finally, his death and funeral in 1820 were, of course, also of note. As Catholic Emancipation became an even more socially and politically contested topic of the time, Drennan’s funeral organisation made a posthumous point. “Let six poor Protestants and six poor Catholics get a guinea apiece for carriage of me, and a priest and a dissenting clergyman with any friends they choose.”

Oh, and on the way to his burial in Clifton Street graveyard they paused at the Royal Belfast Academical Institution (also known as Inst.) as he was also a founder of this prestigious school in 1814, which exists to this day.

When it opened, Drennan said the aim of the school and college was “to diffuse useful knowledge, particularly among the middling orders of society, as one of the necessities rather than of the luxuries of life; not to have a good education only the portion of the rich and the noble, but as a patrimony of the whole people”.

Top lad.