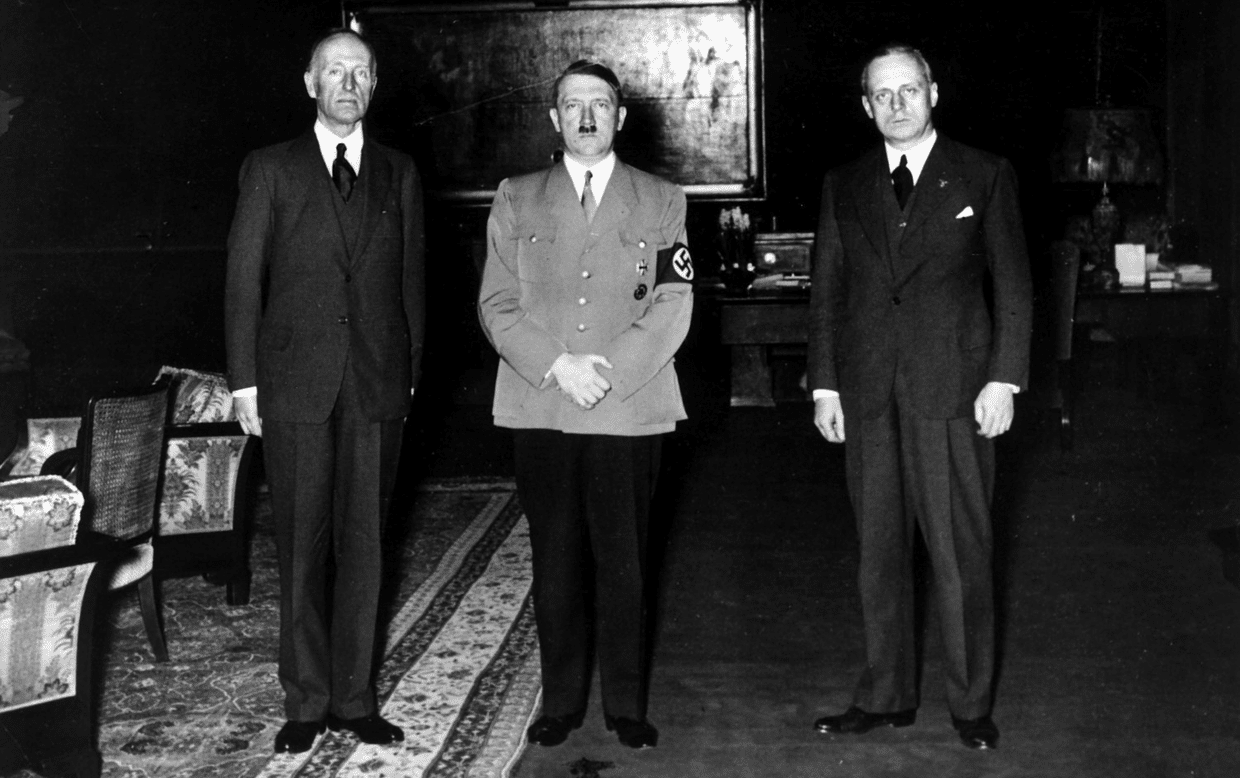

In May 1936 Nazi government minister Joachim Von Ribbentrop arrived at Newtownards airfield in County Down in a three-engined airplane together with a group of SS men. “Swastikas Over Ulster” was one local newspaper headline. Van Ribbentrop was on his way for a four day stay at Mountstewart, the home of former Stormont education minister Lord Londonderry (or Charles Stewart Henry Vane Tempest Stewart) to you and me. The Lord had been the British government’s Secretary of State for Air until 1935 and was still the Lord Privy Seal and the Leader of the House of Lords when he embarked on six visits to Berlin between 1936 and 1938, meeting with Hitler on numerous occasions.

Although no longer in the Air Ministry he felt he could utilise his military experience to prevent war with Nazi Germany. He also had a

But nobody at that time could have envisaged that by late 1938 a refugee settlement farm would be in the making at Ballyrolly House, a derelict stone farm, just six miles away from Mountstewart at Millisle on the Ards Peninsula. A refugee haven which would be home to over 300 Jews escaping Hitler and Von Ribbentrop over the next decade. Most were children from Germany, Austria, Hungary and Czechoslovakia.

The systematic attack of Kristallnacht on November 9th, 1938 shook the complacency in many sectors of European society about the nature of Nazism. In London the Refugee Childrens Movement was formed. Mainly an amalgamation of Jews, Methodists and Quakers, they became responsible for the organisation and transportation of 10,000 Jewish children on block visas away from the Nazis which became known as the Kindertransport. Aged from 3 months to 17 years old, some travelled alone. Virtually none saw their

Ballyrolly House was 20 miles from Belfast sitting on 70 acres of land outside Millisle. To become known simply as ‘The Farm’ it was owned by a local man Lawrence Gorman. Over drinks in the famous Mooney’s bar, in Belfast’s Cornmarket in May 1939 a lease was signed between Gorman and Barney Hurwitz, the President of the Belfast Jewish Congregation.

A Home For Aid hostel had already been established at Cliftonpark Avenue in North Belfast, a building that I taught in many times in the 2000s and also the childhood home of former Israeli President Chaim Herzog. It became the co-ordination point for the arrival of the first children and a handful of adults to oversee life on The Farm.

The first kids arrived via Belfast in the summer of 1939. A typical summer’s day saw heavy rainfall and on the first night they slept in dripping wet tents set up in the fields. On the second day they were relocated to a cowshed and an old stable block would be their dining room. Toilet facilities were virtually non-existent, with latrines being quickly dug. The previously deserted stone farmhouse was to be converted into a liveable functioning building and through time new outbuildings were constructed. Barns and outhouses were utilised for storage of belongings, long wooden huts were built as dorms and eventually flushing toilets and functioning showers were introduced.

In time a small synagogue was fashioned, and the addition of a games room with billiards and table tennis was understandably popular. Money was raised by the German Refugee Committee based in Belfast and supported by both the Catholic and Protestant church communities.

Much activity saw children weeding fields and removing stones, rocks and thistles so the adults could then plant crops of grains and

Livestock was acquired with nearly 2,000 chickens, eight cows and, impressively, two large Clydesdale horses. Of course, the kitchen was Kosher, and the farming was run on a Kibbutz model. In addition, children of all ages were initially paid a shilling per week, later rising to a half crown.

It was a remarkable venture.

Despite the early suspicions of locals towards German-speaking children suddenly living among them, the kids were taught at Millisle primary school. The head teacher John Palmer assigned each refugee child to sit with a local pupil to enhance their integration and familiarisation with each other and assisting in their learning of English (rumours that some of their classmates from Greyabbey got confused and ended up becoming fluent in German have never been proven). Older children progressed to local secondary schools in Newtownards after the age of 11. Delivering ordinary childhood experiences remained the goal as much as possible.

In addition, incredible as it sounds, the refugees from Germany and Austria, both adults and children, were categorised as “enemy aliens.” They were often restricted to designated areas, subjected to stricter night curfew, registered on the Alien Registration book and required police permission to leave the farm even for one evening.

The attempts to build a thriving, positive and supportive farm community could not entirely negate the reality of their plight, and for

Visits to the Regal Cinema in Donaghadee were a regular treat, involving a 3 mile walk or cycle ride along the coastline from Millisle, and also gave the children the opportunity to watch newsreel footage of the war in Europe. Many of the children became increasingly alarmed at the prospect of a Nazi invasion of Britain and Ireland, which having escaped the Nazis once must have been a horrific vista.

By 1945 footage of the liberation of the concentration camps was being screened, creating a dawning awareness in the group of the fate of so many of their friends and families who hadn’t managed to escape like them. Most were now orphans and had to carve out a new life for themselves with no family left to support them.

After the end of the war The Farm continued operating until its closure in 1948. Many of the residents moved on to live in Britain, Canada and the USA while others stayed in Northern Ireland, studying in Queen’s University or working for local businesses. Child refugee and Farm resident Josef Kitzler stayed and settled in Ulster and became a successful businessman. In the mid-1960s he became a board director at Glentoran Football Club in east Belfast.

Little remains at Ballyrolly Farm, other than the once again derelict stone house. Until recently there has been little coverage or discussion about this remarkable story of refugee support, though awareness has increased in the last decade particularly with anniversaries such as VE day and the farm becoming a Listed Building. Hopefully this will continue.